Globally, around 44 million teachers are needed to ensure universal primary and secondary education by 2030, with the greatest need in Sub-Saharan Africa followed by Southern Asia.1

Gender gaps in the teaching workforce

In addition to the widely acknowledged shortage of teachers within crisis settings around the world, there are also gendered disparities across the global teaching workforce. In many places, women are disproportionately highly represented in early childhood and primary education, and underrepresented in secondary and higher education – particularly in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and STEM subjects. In crisis-affected contexts, this fall in the proportion of female teachers as students move through an education system is particularly pronounced. The available data in 32 of the crisis-affected countries in the latest Mind the Gap report shows that female teachers make up 90% of pre-primary teachers, but just 38% of secondary and 31% of tertiary-level teachers. There is some evidence that the situation is even more extreme in some contexts – for instance, data shows that within refugee camps in Benishangual-Gumuz, Gambella, and Tigray in Ethiopia, 90% of teachers at all levels are male.2

Closing these gender gaps in the teaching profession and developing a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the classroom is important to improving the equity, diversity and inclusion of education systems. Female teachers’ presence in education systems is generally associated with expanded educational opportunities and attainment for girls.3 These teachers act as role models and can play an important role in shifting discriminatory gender norms, and often play a key role in encouraging communities to send girls to school and assuring them that girls are safe there.4 For instance, evaluation of work by Plan International in Nigeria’s Borna and Yobe states, where female teachers received training and engaged in community outreach work, found an increase in female learners’ enrollment and positive changes in community members’ support for girls’ participation in education.5

Gender gaps also persist in leadership. Although research and data availability around the experience of women in school leadership positions has improved rapidly in recent years, it remains the case that few women occupy school leadership positions. Research suggests that female leadership in schools can have positive impacts: the PASEC data on education systems in Francophone Africa, for example, shows that in a school with a female principal, all students performed better in reading and mathematics.6 Meanwhile, UNICEF Innocenti’s Time to Teach research suggests that female school leaders are more likely than their male counterparts to actively encourage school attendance and sensitise teachers on how their attendance influences student outcomes.7

Addressing barriers to entry and retention

Barriers to females entering and staying in the teaching profession persist around the world and can be exacerbated in contexts and areas facing conflict, crisis, and hardship. They include a lack of educational prerequisites among women to access teacher training colleges, high levels of harassment and violence, unsupportive teacher management policies, poor pay and working conditions, and lack of pathways for refugee teachers to become nationally registered teachers.

Measures such as scholarships, stipends, and alternative routes into teaching to support women to enter and remain in teacher training programmes are important steps to increase the number of qualified female teachers. There are many routes into teaching that have been developed in emergency contexts. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, where the vast majority of teachers are male, UNHCR has recruited female Rohingya refugees as teaching assistants to begin to address the gender disparity. These teaching assistants support girls in the class with challenges they are facing and are considered role models. In Sierra Leone, the Girls’ Access to Education programme (led by Plan International and funded by the Girls’ Education Challenge) recruited young women from the local community who had been unable to complete secondary school to become learning assistants, working in the classroom and undertaking a training programme that enables them to apply to teacher training college. Successful programmes also remove financial barriers to training and pay stipends both during training and once hired.

In Liberia, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda, researchers found various other barriers to women entering and remaining in teaching, including requirements for safe housing and caring responsibilities. Poor access to electricity, water, healthcare, markets, and good quality housing made taking up posts in hardship areas particularly problematic for women.8 In such contexts, teacher management policy changes could help to address these challenges by creating better conditions for prospective female teachers. For example, providing a greater number of houses for teachers, safe transport options for female staff, and facilitating relocation to nearby towns for pregnant and lactating mothers to access medical services more easily, may all help to improve the working lives of female teachers as well as their motivation to stay in the profession. Meanwhile, further incentives can be provided for female teachers working in remote areas to support recruitment and retention. This was seen in the Restoring Education and Learning Program in Yemen, funded by the World Bank and Global Partnership for Education, where additional payments to female teachers working in very remote areas supported their retention.9

Funding initiatives that support female teachers’ safety and progression should be prioritised by donors and alternative pathways into leadership positions should be explored to address the barriers that women continue to face in accessing training due to timing, travel and caring responsibilities.

Supporting teachers to support learners

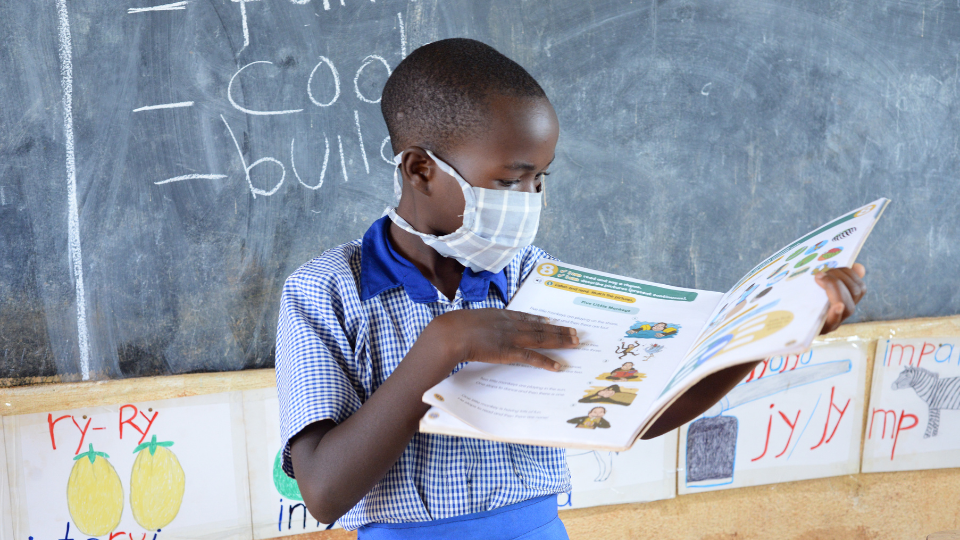

Prioritising teacher wellbeing through support and effective professional development is also essential in addressing the challenges of teaching and supporting learners – especially girls – in crisis-affected settings.

Teachers are asked to foster a sense of belonging and wellbeing among their students, but it is often forgotten that refugee teachers in particular are often dealing with the same stress and trauma as their students and need adequate support and training to manage this as part of their teaching – and often pastoral – role. During research for the Mind the Gap report, Christine Mwongera, a member of the Refugee Education Council, which advocates for effective resources and respond to trauma in schools, told us about her experience as a national teacher in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya:

“We need to provide more opportunities to grow and have professional development and support. I really crave an opportunity where I can gain the skills to help the students, where I can develop professionally so that I can help students with psychosocial support and their trauma, where I know if I see a student behave in a particular way, then I am able to be alert, to know that this person will need help. I am working extra hours, but I don’t feel valued because my extra needs are not being met.”

Support structures should be put in place to enable a focus on teacher wellbeing with guidance and counselling available to help teachers be responsive to the challenges they face and the responsibilities they take on for children’s safety and wellbeing in crisis settings.

Our research also identified the need for governments and education delivery partners to ensure that all teachers have access to high-quality professional development, including disability-inclusive education. This enables them to learn practical and relevant strategies for including children with disabilities in mainstream settings so that they can feel confident and capable in teaching diverse learners. Leonard Cheshire’s project experience in Kenya showed that after inclusion training, teachers interacted more positively with girls with disabilities in their classrooms and no longer used corporal punishment. 10 Meanwhile, the World University Service of Canada found that after training, girls with disabilities felt that their teachers were much more likely to be supportive of their learning needs.11

Our research also identified the need for adequate teacher training around the delivery of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE), which seeks to provide learners with the necessary skills and knowledge to make informed and meaningful decisions about their sexual health and wellbeing, rights and relationships. Teachers need adequate preparation and quality materials to effectively deliver CSE education, to avoid reinforcing harmful gender stereotypes or norms, and to feel comfortable tailoring the curriculum to respond to learners’ contextual needs. A good example of this can be found in Mali, where CARE’s Janndé Yirriverre Programme co-developed CSE modules through community consultations and with the Ministry of Education. Teachers were trained to deliver the modules in stages and, with in-school coaching support, use a facilitative mentoring approach in sessions. This addressed teachers’ initial reluctance to deliver the content, as well as hesitancy from parents and the community.

Overall data on female teachers in crisis settings continues to be limited, patchy, and difficult to collect, with notably little disability-disaggregated data available. With this lack of evidence around what works to support women to progress into leadership positions and limited research into effective strategies to support and retain female teachers in insecure environments, data collectors and collators should collaborate with local actors to ensure the voices of female teachers are heard and prominent. This will better enable us to understand how to tailor solutions appropriately whilst also ensuring that data on teachers in refugee settings is comprehensive and disaggregated – ultimately contributing to more inclusive, equitable education systems which benefit girls in crisis-affected settings worldwide.

These insights are drawn from the latest Mind the Gap report, produced by the Inter-agency Network on Education in Emergencies (INEE) and EDT. These reports, published in each of the past three years, support the Charlevoix Declaration of Quality Education commitment to enhance the evidence base and monitor progress towards gender-equitable education in crises. The series highlights the ongoing, increasing need for investment in gender equality in and through education for those in crisis settings, drawing on data and research on the state of women and girls’ education in 44 crisis-affected countries and highlighting case studies of emerging good practice.

This year’s report, Mind the Gap 3: Equity and Inclusion in and through Girls’ Education in Crisis, includes three thematic chapters which draw on recent research and case study programmes to discuss recruiting and retaining female teachers, girls with disabilities and gender-responsive education and sexual and reproductive health (SRHR) education in emergencies. In the accompanying policy paper, Closing the Gap 3: Promoting Equity and Inclusion in and through Girls’ Education in Crisis, we recommend actions for government, donors, civil society, data users and other education personnel addressing the themes of the report.

Please contact our Research and Consultancy team to find out more.

1 UNESCO and the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030. (2024). Global Report on Teachers. Addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. Paris: UNESCO. [Available online https://teachertaskforce.org/what-we-do/Knowledge-production-and-dissemination/global-report-teachers. Accessed March 2014].

2 Bengtsson, S., Fitzpatrick, R., Hinz, K., MacEwan, L., Naylor, R., Riggal, R., West, H. (2020). Teacher Management in refugee settings: Ethiopia. Reading: Education Development Trust and UNESCO IIEP. [Available online. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373686/PDF/37a686eng.pdf.multi Accessed March 2024].

3 International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030 (2021) Closing the gap – Ensuring there are enough qualified and supported teachers in sub-Saharan Africa. Paris. UNESCO. [Available online https://teachertaskforce.org/knowledge-hub/closing-gap-ensuring-there-are-enough-qualified-and-supported-teachers-sub-saharan. Accessed March 2024]. Psaki, S., Haberland., N. Mensch, B., Woyczynski, L., Chuang, E. (2022). Policies and interventions to remove gender-related barriers to girls’ school participation and learning in low – and middle- income countries. A systematic review of the evidence. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 12, e1207 http://doi/10.1002/cl2.1207

4 Sperling, G. B., Winthrop, R., Kwauk, C. (2016). What works in girls’ education. Evidence for the World’s Best Investment. Washington, DC. Brookings Institution Press.

5 Plan International. (2023). Unpublished monitoring data for the Plan International Project “Educating Vulnerable and Hard to Reach Adolescents Girls in Northeast Nigeria.” Data collected January-December 2022.

6 Programme d’Analyse des Systéms Éducatifs de la CONFEMEN (PASEC). (2020). Synthesis PASEC 2019: Quality of education systems in French-speaking sub-Saharan Africa: Performance and teaching-learning environment. Dakar. PASEC.

7 Jativa, X., Karamperidou, D., Mills, M., Vindrola, S., Wedajo, H., Dsouza, D., Bergmann, J. (2022). Time to teach: Teacher attendance and time on task in West and Central Africa. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti. [Available online https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/1565-time-to-teach-teacher-attendance-and-time-on-task-in-west-and-central-africa.html accessed March 2024].

8 Stromquist, N. P., Klees, S.J., Lin, J. (2017). Women teachers in Africa: Challenges and possibilities. Abingdon. Routledge.

9 UNICEF. (n.d). The Restoring Education and Learning project. [Available online https://www.unicef.org/yemen/restoring-education-and-learning-project. Accessed March 2024]

10 Tan, D. (2020). Être fille & handicapée en Afrique de l’Ouest: La situation educative en question Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso [Being an girl & disabled in West Africa. The educational situation in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso]. Humanity & Inclusion. [Available online. https://genrehandicapao.hubside.fr/. Accessed March 2024].

11 C.A.C International. (2022). Kenya Equity in Education Project, KEEP II endline evaluation. Girls’ Education Challenge. [Available online https://girlseducationchallenge.org/media/hasbi2xr/keep-ii-endline_final-for-web.pdf. Accessed March 2024].