Rwanda achieved gender parity in access to primary education in 2001, but gaps remain in academic outcomes, transition rates to secondary school and career aspirations. Education Development Trust is committed to advancing our understanding of ‘what works’ in girls’ education with a goal to establish gender equitable school systems which empower both girls and boys. As part of the next phase of our Building Learning Foundations (BLF) project in Rwanda, we are launching girls’ clubs in 20 schools to provide a safe space for girls to come together, learn life skills, build their confidence and improve their school performance.

To maximise the girls’ clubs pilot success, Education Development Trust colleagues and the BLF Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) team have gathered insights through a girl-centred situational analysis. Drawing evidence from past interventions, literature reviews and consultations with key stakeholders – including the girls themselves – this analysis reveals important context for the pilot’s design. It reveals the attitudes, behaviours, knowledge and aspirations of students, caregivers and teachers.

Girls do not receive the same level of support for schooling as boys

Our analysis confirms how traditional gender roles impact girls’ time and ability to study, highlighting the differences in the day-to-day domestic responsibilities of girls compared to boys. Almost all girls (92%) spent time on domestic chores daily compared to just 56% of boys. Indeed, ‘domestic work’ and ‘caring for someone else with an illness or disability’ were also more common reasons for absenteeism among girls than boys. At the same time, boys reported spending more time with friends and classmates and, importantly, more time studying compared to girls. They were also more likely to use devices for learning activities.

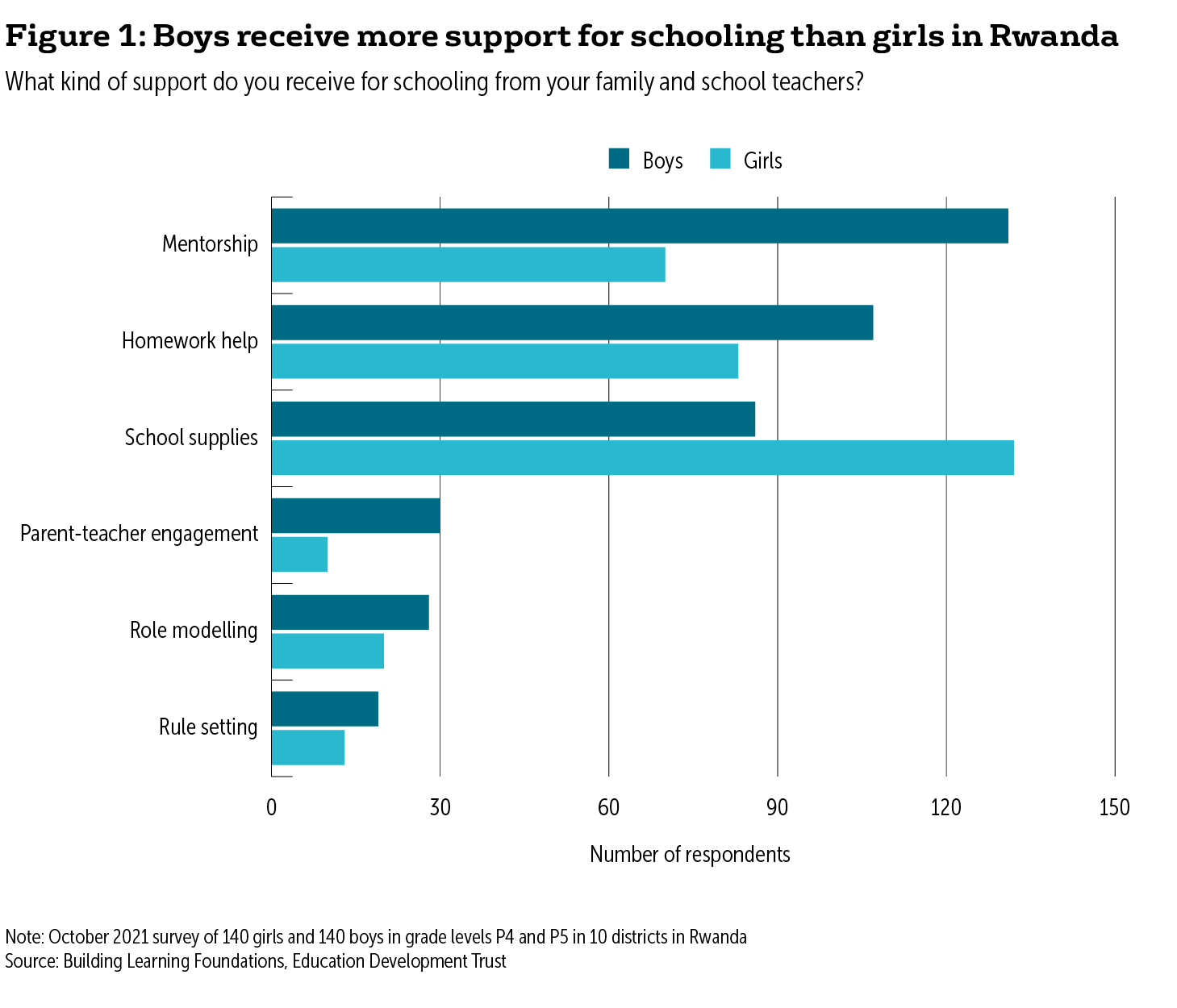

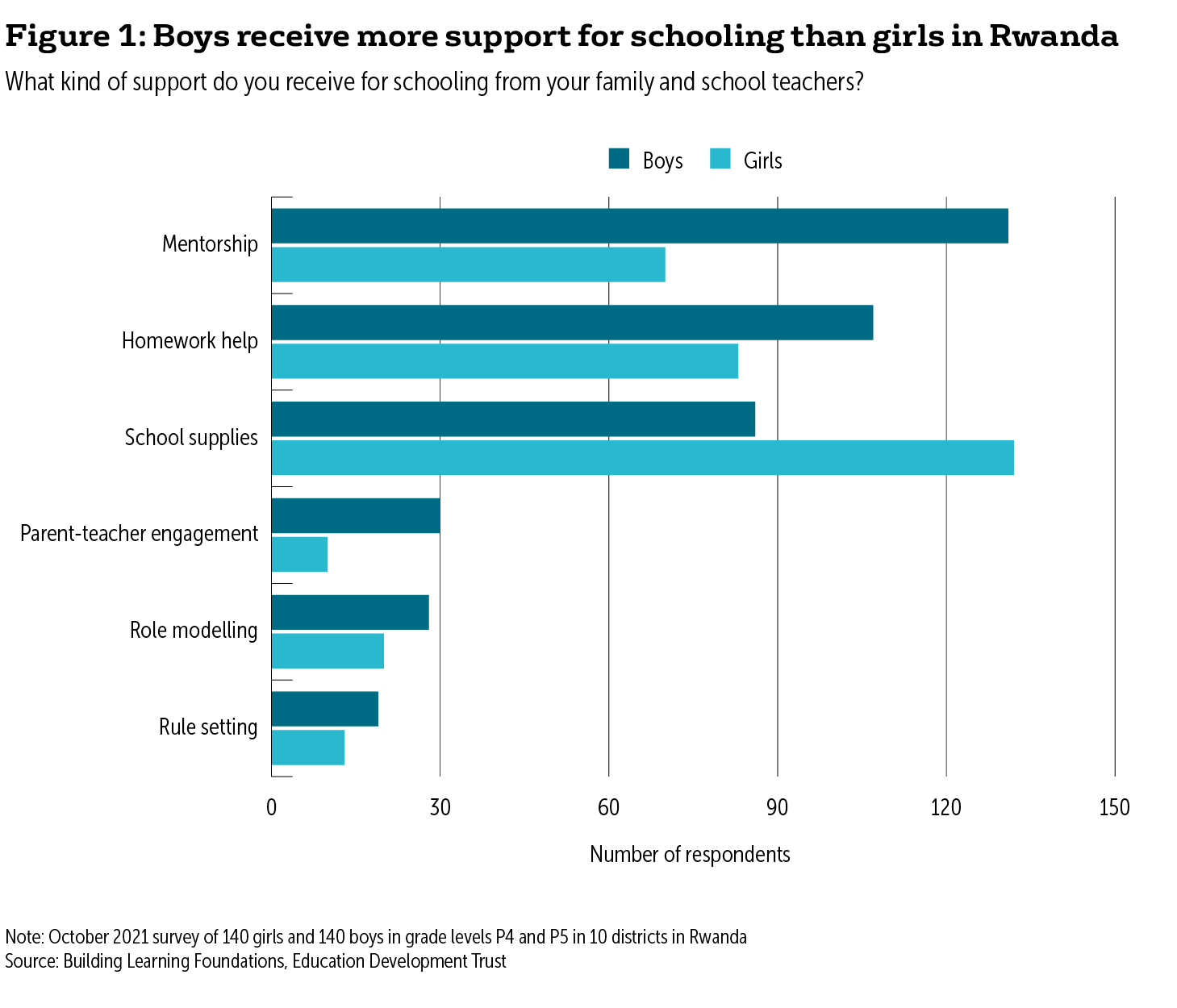

The lack of emotional support received by female students compounds the challenge of less time spent studying. Girls reported that teachers were less likely to support their educational goals compared to boys. Meanwhile, more boys reported receiving homework help, mentorship and parent-teacher engagement compared to girls, although more girls reported receiving school replies (see figure 1). Particularly useful in the context of developing girls’ clubs was a question about who students go to with a problem: 84% of girls compared to 44% of boys would prefer to speak to someone of the same gender. Girls also said they would be less confident generally expressing their opinions in the presence of boys and/or men. These are critical insights in a country where 87% of school leaders are male.

Gendered misconceptions are held by boys, girls, caregivers and teachers

The objective of the BLF programme is to improve English literacy and Mathematics amongst Primary 1 to Primary 5 pupils. Our findings suggest addressing widespread gendered misconceptions may be central to ensuring good performance among girls in particular subjects – data showed only 29% of girls and 26% of boys believed that both genders were equally skilled in Mathematics. Furthermore, most caregivers, both male and female, corroborated the view that girls and boys are not equally skilled in maths and science. These same views were also, disappointingly, repeated by teachers and school leaders – of both genders.

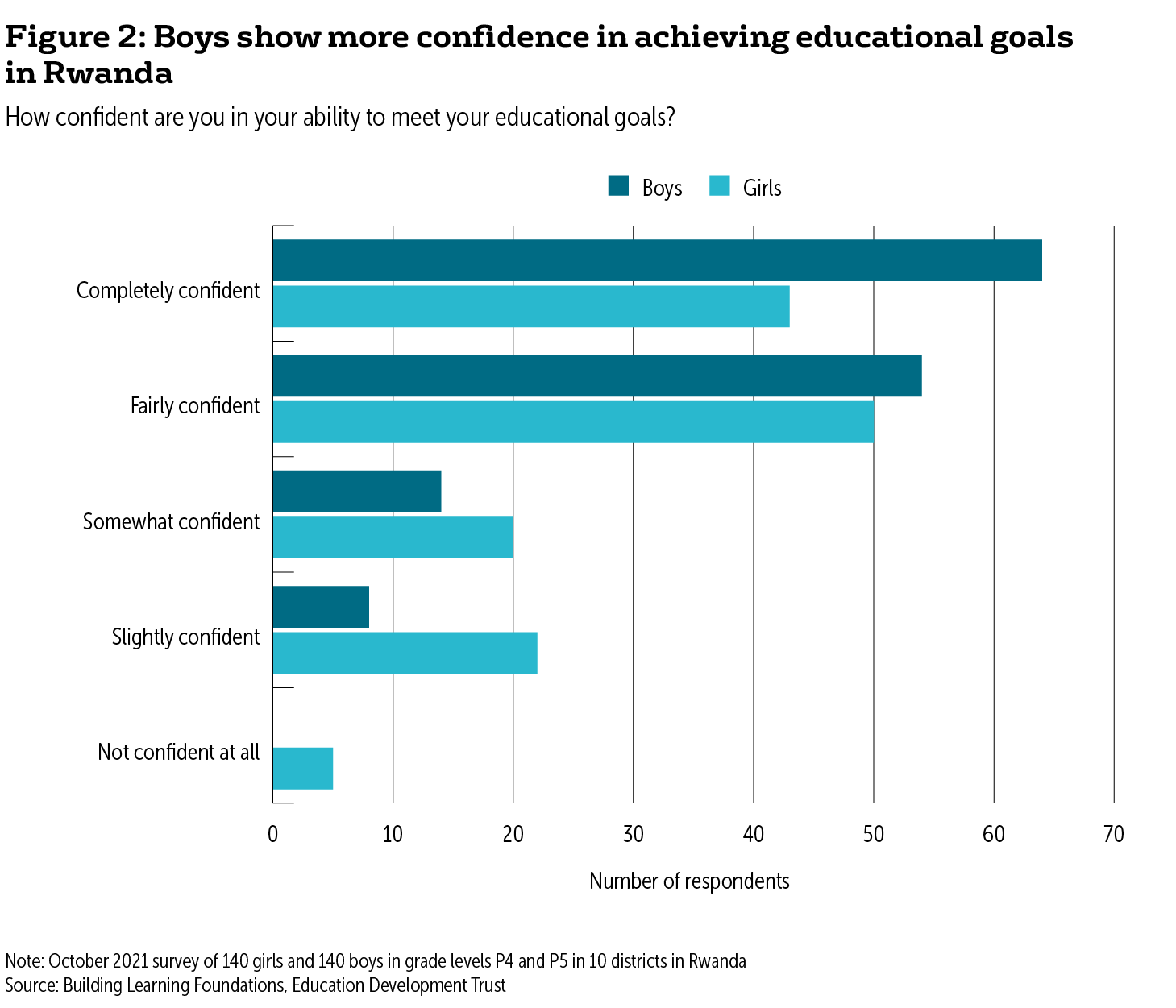

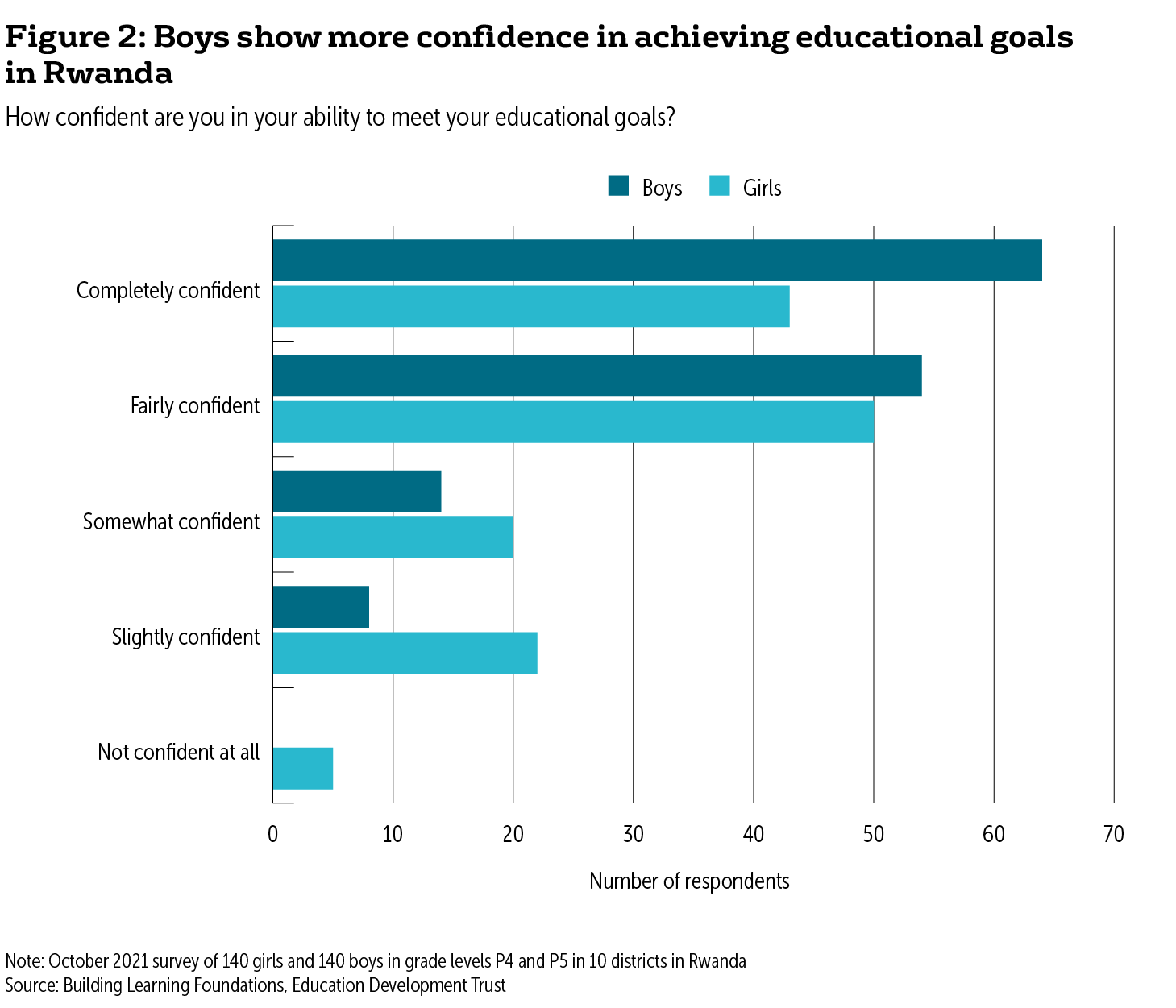

Nevertheless, a small number of schools had initiatives for encouraging girls in STEM and supporting their transition to secondary school. But perhaps unsurprisingly, girls were overall less confident in achieving both their educational and economic goals (see figure 2). A significant number more boys than girls stated they were ‘completely confident’ with their ability to meet their educational goals’, while five girls stated they were ‘not at all confident’ – compared to zero boys.

Further misconceptions were articulated in relation to the menstrual cycle and pregnancy and one in ten girls recorded menstruation as a reason for school absence. Knowledge of these topics was lacking to a greater degree among boys – pointing to the benefits of including boys in the clubs’ activities in some way.

Girls’ clubs have the potential to counteract and dismantle damaging gender dynamics

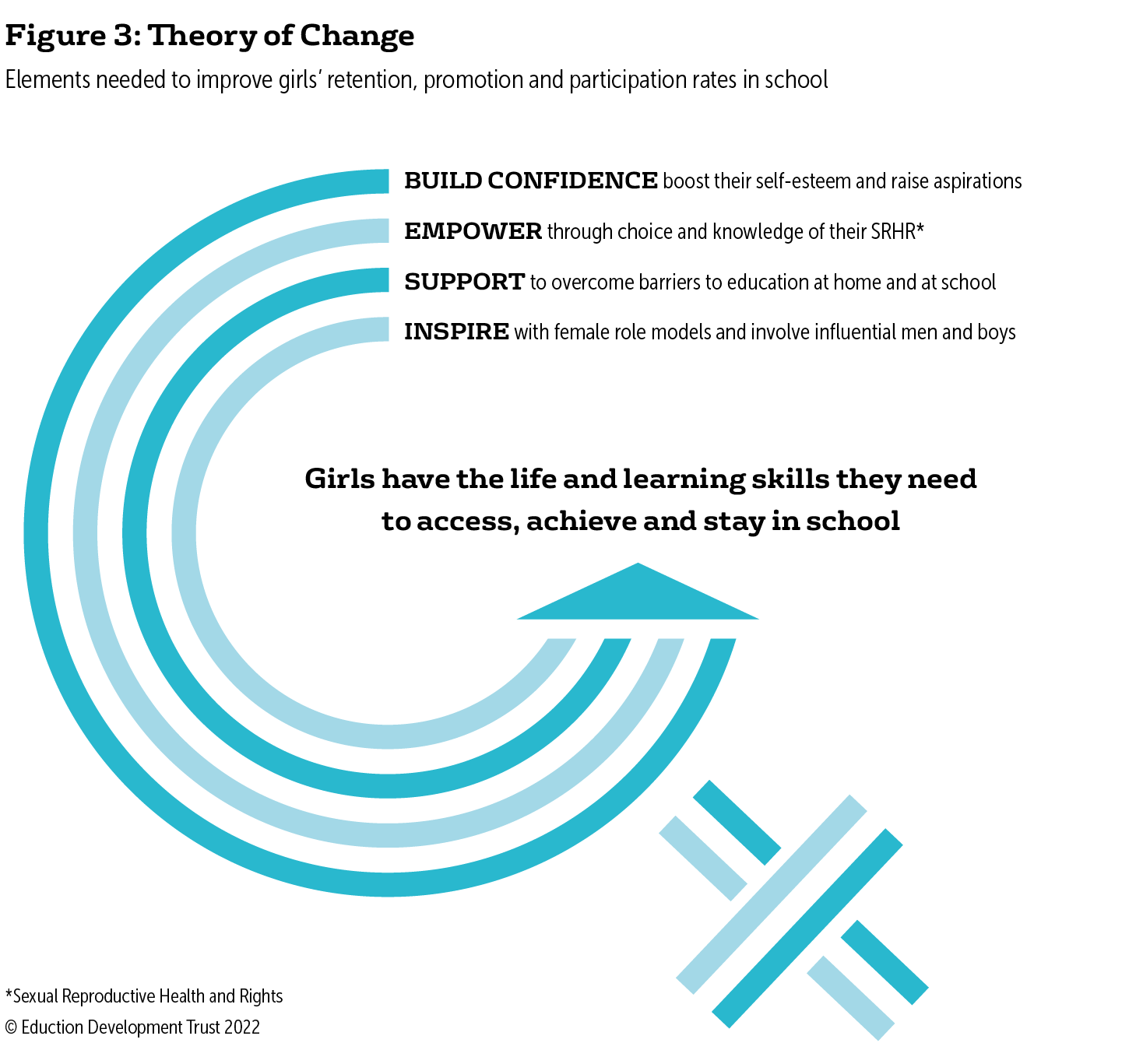

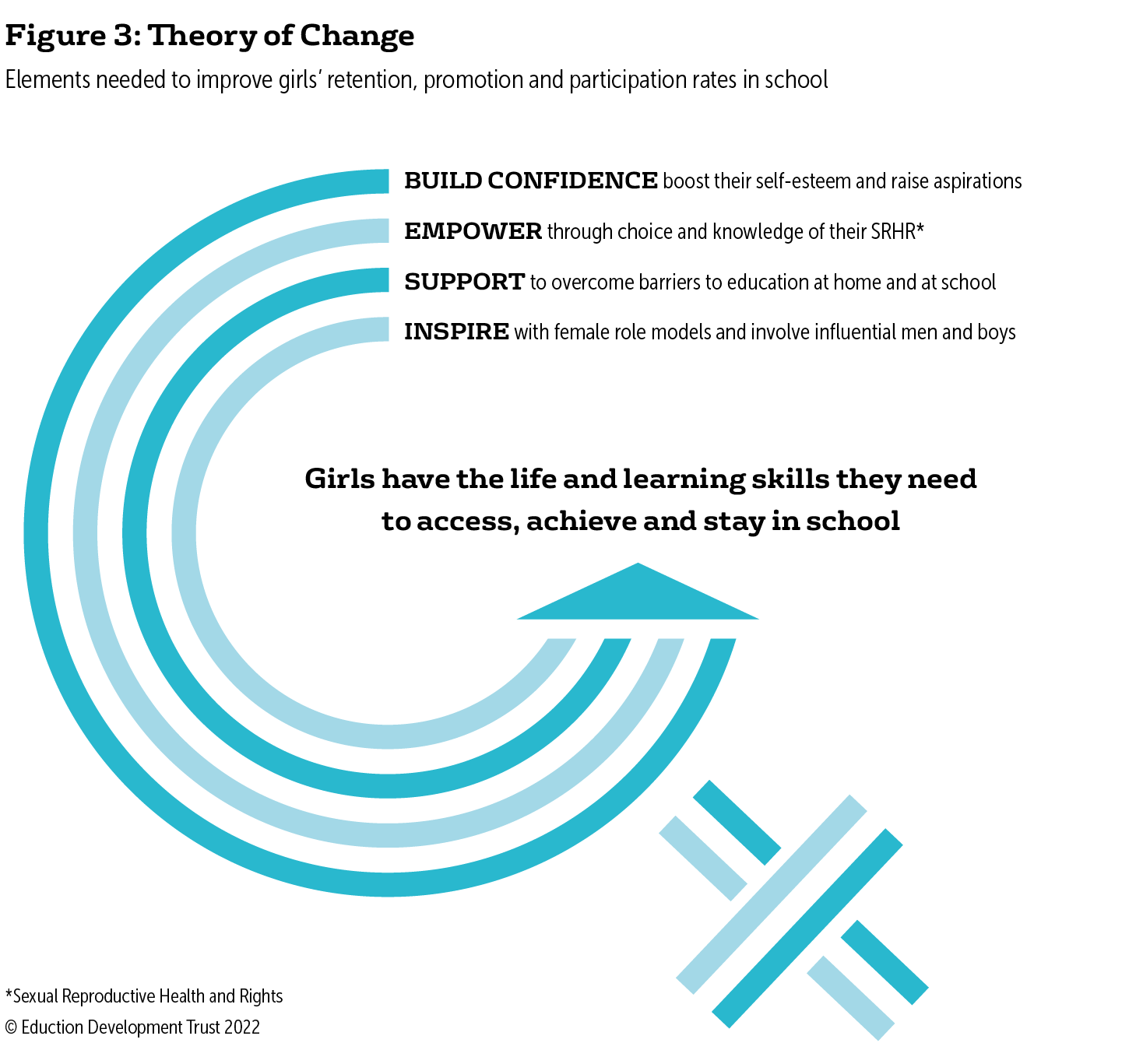

Although the latest figures show girls outnumbering boys in primary school in Rwanda, this analysis demonstrates demand for additional, gender-sensitive interventions. Girls generally reported receiving less support in school and at home, having less confidence and lower aspirations for themselves and higher concerns for their safety and future. Despite the relatively small sample, this research shows the clear gender dynamics at play and how they affect primary school girls in Rwanda. It has also provided a basis for designing a logical Theory of Change for our programme, showing how a combination of self-esteem boosting, knowledge, practical skills and role models are needed to improve girls’ retention, promotion and participation rates in school (see figure 3).

The overall goal of the clubs will be to provide members with a safe, supportive, fun and inspiring environment in which to achieve the following outcomes:

- Enhanced life and learning skills

- Increased confidence in achieving academic goals, including in Mathematics

- Sustained recognition of girls’ learning gains and achievements

- Increased knowledge about sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR)

- Increased awareness of how to identify and report abuse.

Our girls’ clubs design is informed by evidence and complements broader, holistic interventions

Over a five-month period, we will pilot girl-focused ‘Breaking Barrier Clubs’ which will support overage P4 and P5 girls approaching puberty who are at higher risk of dropping out of school. Our girls’ club model will reflect the lessons from this baseline study which will also be used to make improvements to the broader Building Learning Foundation intervention.

Crucially, we acknowledge the need to involve boys and men, family members and school staff, as well as girls, in order to tackle the system-wide biases and gendered attitudes which hold back girls’ learning. We share the below recommendations on girls’ clubs and supporting interventions, disaggregated by stakeholder, to support colleagues across the global education community who may benefit.

With girls:

- Provide pre-adolescent and adolescent primary-level female pupils with a girls-only safe space in the form of a girls’ club that meets regularly under the guidance and oversight of a carefully selected female teacher/mentor.

- Develop a fun, inspiring and informative girls’ club curriculum that focusses on life and learning skills. The pilot will follow a holistic three-pillar curriculum:

- Me, my mind and body – covering topics such as SRHR, puberty, violence, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and menstrual hygiene

- Me, my school and education – looking at aspirations, confidence, personal care and role models

- Me and my community – considering burden of household chores, support systems, community give back and financial life skills etc.

With boys:

- Solicit the strategic involvement of male pupils in a select number of mixed-gender club sessions, showing them the potential of their role in preventing and responding to discriminatory attitudes and practices against girls.

With teachers and head teachers:

- Provide unconscious bias training to cultivate an environment in which deeply rooted gender biases can be safely exposed and examined, creating space for normative change.

- Provide training in Gender-Responsive Pedagogy (GRP) and ensure appropriate follow up to assess its implementation in redressing classroom gender dynamics.

- Reinforce understanding of how to identify and report abuse according to pre-established reporting and referral pathways.

- Ensure that girls’ learning gains and achievements are acknowledged and celebrated.

- Proactively plan, monitor, and budget for targeted interventions to retain girls in school, encourage their promotion to secondary education and beyond, as well as their engagement in STEM subjects (including pregnant/lactating girls and girls with diverse disabilities).

With parents and other primary caregivers:

- Engage with male and female caregivers through community-based mentorship to ensure they understand and value girls’ education.

- Discuss strategies for creating home environments supportive to girls’ learning and ensuring girls have sufficient time and resources to dedicate to their schooling.

BLF is a UK government funded programme which aims to improve the quality of teaching and leadership in Rwanda’s primary schools. The programme is being delivered by Education Development Trust in partnership with Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) and the British Council.