Global

View all Research

Teacher development

System change

Improving school systems at scale

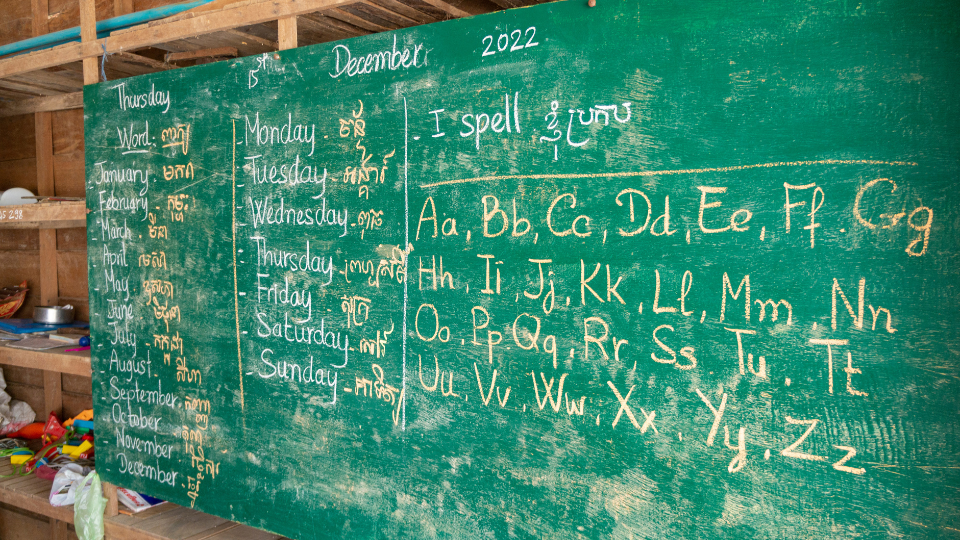

Language learning

Ownership and management of schools

School-to-school collaboration

Early years

Edtech

Accountability

Employability and Careers

Refugee education

School leadership

Girls education

Case study

Covid-19

Climate change

View all Podcasts

Exploring school improvement through external review with Noelle Buick and Valerie Dunsford

The nuances of applying research to real world teaching with Cat Scutt, Emma Gibbs and Dr Richard Churches

Strengthening the connection between young people and their futures with Oli de Botton, Mark De Backer & Wendy Phillips

Harnessing the collective power of peer review with Maggie Farrar and David Godfrey

Achieving a gender-responsive pedagogy with Nora Fyles, Ruth Naylor and Rosa Muraya

The ‘golden thread’ helping to retain ECTs with Sam Twiselton OBE & Dr Nicky Platt

How leaders of learning are improving education in Rwanda with Amy Bellinger and Jean-Pierre Mugiraneza